The Talent Wars: Why the Battle Has Moved and Where It Is Being Won

The talent war did not disappear. It shifted. As demand moves from generalist engineers to infrastructure-capable builders, companies that keep hiring in the same places are quietly losing ground. This piece explores where the real competition is happening now, and why regions like Eastern Europe are increasingly central to winning it.

For years, the tech industry has framed hiring as a war. Companies competing for the same engineers, in the same cities, with ever increasing salaries and even louder employer branding. At times, the metaphor felt exaggerated. At others, it felt uncomfortably accurate.

Today, the talent wars are still real, but they are no longer being fought on the same battlefield.

What has changed is not the demand for engineers. It is the type of engineering capability companies are competing for, and where that capability is concentrated. The shift is subtle enough that many organizations are still hiring as if it were 2018, but significant enough that those organizations are quietly losing ground.

The talent war has not intensified. It has just moved.

What the Talent Wars Originally Meant

The phrase “talent wars” gained traction during a period when software demand dramatically outpaced supply. Cloud adoption accelerated, mobile platforms exploded, and venture capital fueled rapid headcount growth. Hiring success was often determined by speed and visibility.

The war had a clear shape.

Demand focused on generalist software engineers who could ship product quickly. Hiring clustered in a handful of global hubs such as San Francisco, New York, London, and Berlin. Compensation inflated rapidly as companies competed with salary, perks, and brand prestige. Engineers were poached between competitors, often with minimal change in role or responsibility.

The bottleneck was access. Whoever could reach candidates fastest, pay most aggressively, and project the strongest brand tended to win. This model worked until it didn’t.

Why the Old Model Broke Down

Several forces have converged to change the nature of demand.

First, software systems themselves have become more complex. Products are no longer isolated applications. They are distributed systems, integrated with third party platforms, operating under regulatory constraints, and expected to perform reliably at scale.

Second, AI has shifted expectations without reducing complexity. While AI tooling has accelerated certain forms of development, it has also increased pressure on infrastructure. Models need data pipelines, deployment frameworks, observability, security, and cost control. AI does not remove engineering complexity, it relocates it.

Third, remote work has flattened access while exposing capability gaps. Companies can now hire globally, but only if they know what they are actually looking for. Geographic expansion without clarity simply broadens the funnel of noise. As a result, demand has narrowed.

The most contested talent today is not “any engineer.” It is engineers who can design, build, operate, and evolve complex systems over time.

The New Center of Competition: Engineering Infrastructure

In today’s market, companies are no longer competing primarily for specialists with narrow tool expertise. They are competing for engineers who can work across layers.

This includes people who understand back end systems, data flows, and platform trade offs. Engineers who are comfortable with reliability, security, and performance, not as afterthoughts, but as design inputs. People who can reason about failure modes, long term maintainability, and organizational constraints.

Industry data reflects this shift. Roles related to back end engineering, platform engineering, DevOps, and site reliability continue to show persistent shortages, even as hiring in other areas fluctuates. Surveys from large hiring platforms consistently show longer time to hire and higher compensation pressure for senior infrastructure roles compared to front end or application focused roles.

In other words, the war is no longer about volume. It is about capability.

Why AI Did Not End the Talent War

There is a common narrative that AI will reduce the need for engineers. In practice, the opposite is happening at the infrastructure level.

AI accelerates output, but it also raises expectations. Systems must scale faster, handle more data, and operate more reliably. Model training and inference introduce new cost dynamics and operational risks. Governance and compliance requirements increase, especially in regulated industries.

All of this shifts demand toward engineers who can make AI systems work in production, not just in demos.

This is why many companies now report a paradox. They have access to more candidates than ever, but fewer who meet the bar for building and operating modern systems at scale.

The Global Redistribution of Capability

One of the most important, but least discussed consequences of this shift is geographic.

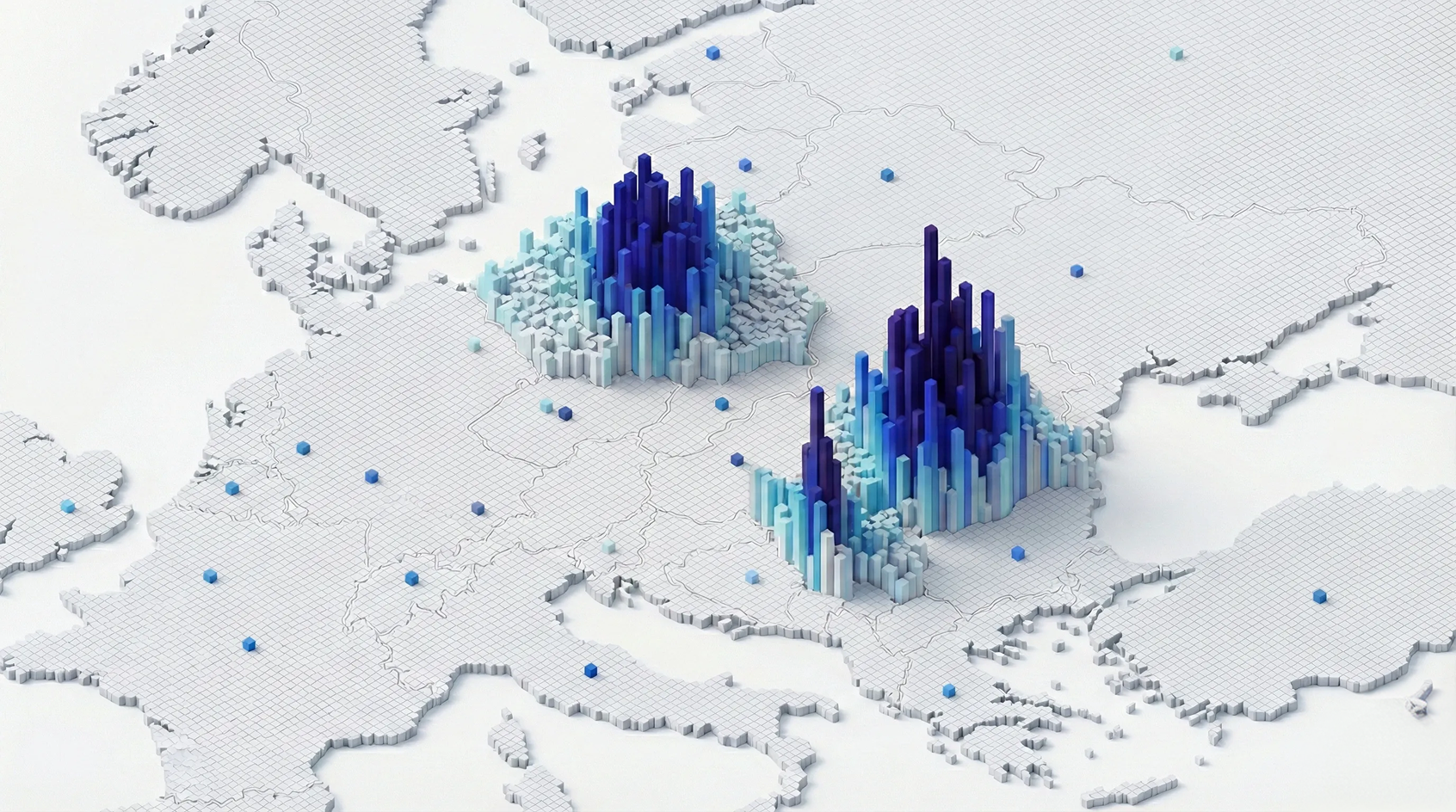

The old talent war assumed that capability was concentrated in a few global hubs. That assumption no longer holds, and arguably has not held for years. What has changed is visibility.

Engineering capability has always been more distributed than a headlines suggested. What is different now is that the skills most in demand are disproportionately strong in regions that built their reputation on depth rather than hype.

Eastern Europe is one of those regions.

Eastern Europe and the New Talent War

Eastern Europe has long served as a delivery engine for global technology companies, with deep representation in systems engineering, back end development, embedded software, and infrastructure work. Many engineers in the region have spent their careers building and maintaining long-lived products rather than short-lived startups, which has shaped a workforce that is comfortable with scale, complexity, and operational responsibility.

Several structural factors explain this strength. Engineering education across much of Eastern Europe has historically emphasized fundamentals such as algorithms, systems thinking, and mathematics. Many engineers were trained in constrained environments, fostering discipline around performance, reliability, and resource efficiency. In addition, a significant portion of the workforce has spent years collaborating with Western European and North American companies, often in regulated or mission-critical contexts.

This has produced a high concentration of senior engineers who are comfortable operating deep in the stack, including:

- Designing and maintaining complex distributed systems

- Working within strict reliability, security, and compliance requirements

- Owning long-term technical decisions rather than short-term experiments

Despite this, the region has not achieved equivalent visibility in mainstream hiring narratives. Headline conversations still skew toward familiar markets, even as real delivery increasingly depends on talent elsewhere. This mismatch between perception and reality creates a growing opportunity for companies willing to change where they look for engineering leadership and depth.

The Geography of Talent

The modern talent market is uneven by design. Demand concentrates around specific skills, while supply is distributed across regions. Cost pressure peaks where demand, visibility, and habit overlap, not where capability is deepest.

This is why companies hiring exclusively in traditional markets face rising costs without corresponding gains in quality. They compete in the most crowded parts of the market for an increasingly narrow pool of candidates.

At the same time, regions such as Eastern Europe remain under leveraged relative to their contribution to real world systems. Strong engineering depth, long established technical education, and experience operating within complex environments continue to be overlooked.

When Hiring Optimisation Stops Working

In response to scarcity, many organizations focus on improving hiring mechanics. More recruiters. Better sourcing tools. Faster pipelines. Stronger employer branding.

These changes improve efficiency, but they do not address the underlying mismatch between where companies look for talent and where durable capability exists. The constraint is no longer speed or effort.The challenge is strategic.

Winning now requires shifting from optimizing individual hires to designing systems that provide long term access to critical skills.

This is where satellite offices and build operate transfer models become relevant, not as cost saving measures, but as deliberate organizational choices.

Designing Long Term Capability

Carbon’s work sits at this transition point.

The question is no longer how to hire faster in competitive markets. It is how to secure lasting access to the capabilities that matter most, before competition intensifies further.

Satellite teams allow companies to anchor engineering capability in regions where depth is high and turnover is lower. Build operate transfer models create ownership and continuity, reducing dependence on constant replacement hiring.

This reflects the reality of modern systems. Complex infrastructure depends on stability. Knowledge compounds over time. Teams perform best when they are built intentionally rather than assembled under pressure.

In this context, hiring becomes less about winning individual searches and more about choosing where to invest.

Capability Over Proximity

Remote work decoupled capability from location. The organizations that benefit most are those that design for this reality intentionally.

This means investing in collaboration, documentation, and leadership that supports distributed teams. It means treating satellite offices as core parts of the organization, not peripheral extensions. It also means committing to regions with long term intent rather than transactional engagement.

Eastern Europe has demonstrated, over decades, that it can support this model when approached as a strategic partner. Depth, continuity, and system level thinking are already present. The opportunity lies in recognizing and building around them.

The next phase of the talent war

Several forces are accelerating the redistribution of talent, and they are structural rather than cyclical.

- System complexity continues to increase. As organizations integrate AI, data platforms, security, and regulatory requirements, demand grows for senior engineers who can operate across layers rather than within narrow specialisms.

- Competition in traditional markets remains intense. Costs continue to rise, hiring cycles lengthen, and the available pool of experienced talent does not expand at the same pace.

- Regions with strong engineering foundations and lower visibility are becoming more contested. As companies look beyond familiar markets, early movers gain an advantage by establishing presence, building trust, and developing teams with long term continuity.

In this environment, the talent war enters a new phase. One defined less by speed and optimization, and more by foresight, commitment, and deliberate capability building.

A different way to win

If everyone is fighting for the same talent, the winners are those who change where they look.

This does not mean abandoning quality or lowering the bar. It means aligning hiring strategy with how engineering actually works today. It means recognizing that capability is global, unevenly distributed, and increasingly infrastructure driven.

The talent war is no longer about access to resumes. It is about access to systems thinking, operational maturity, and long term ownership.

Companies that understand this will not only hire better. They will build teams that last.

Carbon is the go-to staffing specialist for Eastern European and North African technical talent. Trusted by the biggest names in technology and venture capital, Carbon’s hyperlocal expertise makes entering new talent markets for value-seeking global companies possible.

Honouring exceptional talent ®